The Centers for Disease Control recently indicated that our traffic death rate per capita is nearly double the average of other developed nations.

Vision Zero: A Vision for Safer Streets for All

Vision Zero: A Vision for Safer Streets for All

Each year, more than 30,000 people – the population of a city roughly the size of Laguna Hills or Los Gatos – are needlessly killed on American streets and thousands more are injured. Traffic fatalities in the United States hit a seven-year high in 2015, with pedestrians and bicyclists accounting for a disproportionate share.

The Centers for Disease Control recently indicated that our traffic death rate per capita is nearly double the average of other developed nations.

We’ve long considered traffic deaths and severe, disabling injuries to be inevitable side effects of modern life, despite the rising threat they pose. The significant loss-of-life affects our communities in a number of ways, including personal economic costs and emotional trauma to the victims and their families, and significant burden on taxpayers because of emergency response and long-term healthcare costs.

The lack of safety on our streets also compromises the choice to walk or bike, which in turn weakens public health through increasing rates of sedentary diseases and higher carbon emissions.

In 1997, the Swedish parliament addressed these risks by adopting a “Vision Zero” approach to transportation, directing the government to manage the nation’s streets and roadways using policies and practices to implement the ultimate goal of preventing fatalities and serious injuries – elevating Sweden as an international leader in the area of road safety.

When Vision Zero first launched, Sweden recorded seven traffic fatalities per 100,000 people. Today, despite a significant increase in traffic volume, that number is fewer than three – making it one of the lowest annual rates of road deaths in the world. Not only that, fatalities involving pedestrians have fallen almost 50% in the last five years.

By comparison, the number of road fatalities in the U.S. is 11.6 to 12.3 per 100,000 residents (varies by study).

Road-system design should be based on the premise that humans are fallible and will make mistakes, according to professor Claus Tingvall, one of the architects of Sweden’s Vision Zero policy. Understanding this reality “should influence roadway design, where traffic calming, well-marked crosswalks and pedestrian zones, and separated bike lanes can help minimize the consequences of a mistake.” The principles of Vision Zero sum this up: “In every situation, a person might fail. The road system should not.”

The Road to America

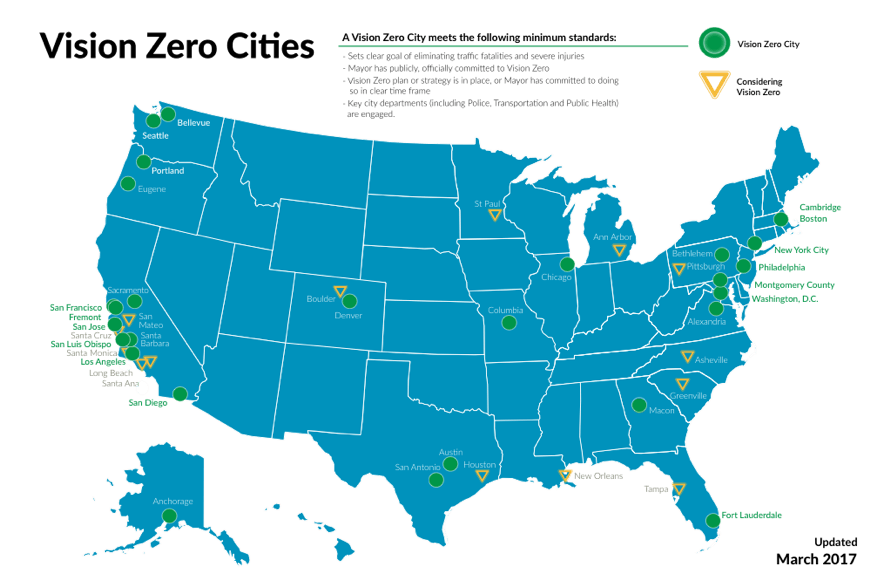

Vision Zero has since proved successful across Europe – and is now gaining momentum in America.

Several states have implemented a Vision Zero approach with dramatic results, including a 43% reduction in traffic fatalities in Minnesota, a 48% reduction drop in Utah, and a 40% decrease in Washington State.

At the local level, cities are also taking note. From Sacramento to San Diego across California and coast to coast from Anchorage to Washington, DC, local governments are getting serious about their commitment to provide safe transportation in their communities, adopting Vison Zero policies aimed at eliminating all traffic fatalities and severe, disabling injuries.

A community can become a Vision Zero City by making a public commitment to eliminating traffic fatalities, creating a plan and time frame to achieve this goal, and engaging residents and key city departments (including police, transportation, public works and public health), school districts and transit agencies.

Core Strategies for Reaching Vision Zero

Lower Speed Limits to Increase Safety.

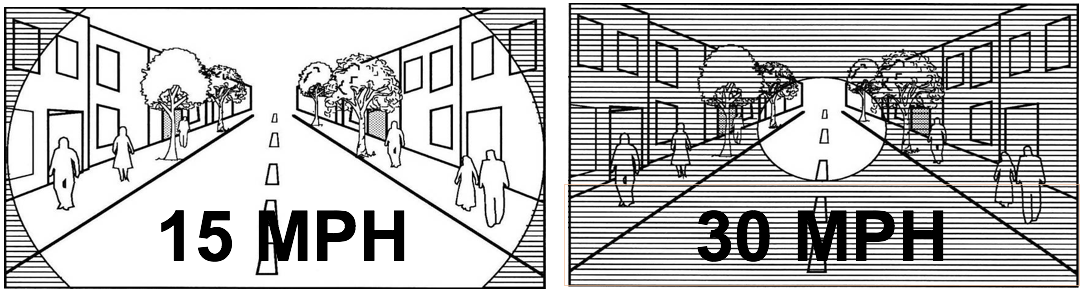

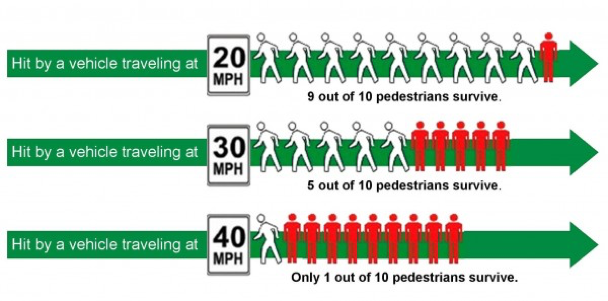

Too many drivers think they have the skills to drive fast, but driving is a complex task, and a distraction can have tragic results at high speeds. Speed can quickly reduce a drivers’ field of vision and the ability to see pedestrians, reducing their ability to react and avoid a crash in a timely fashion (as seen in the figures below).

Speed also intensifies the severity of a crash. Pedestrians are much more likely to survive being hit by a car going 20 MPH (90%) than 40 MPH (10%). Sweden’s Vision Zero policy doesn’t allow a higher speed than 18.6 mph [30 kilometers per hour] in areas with protected and unprotected road users.

Redesign Streets for All Users.

Sweden’s success came from engineering solutions more than enforcement, according to Matts-Åke Belin, traffic-safety strategist for the Swedish Transport Administration and one of Vision Zero’s key architects. “Where you allow the driver to make a turn at the same time you have a green light for a pedestrian, you have put the whole safety prevention or risk reduction on these two people. And if someone makes a mistake, actually, then you are creating a problem for these road users. If you want to support them, maybe you need to give priority to the pedestrian, and the car has to wait, and then you have a green arrow.”

This is especially critical for vulnerable users, including children and seniors, bicyclists, pedestrians and people with disabilities.

In the U.S., there is a growing movement to create “complete streets” that address the need to provide safe, easy access and greater mobility for people of all ages and abilities, especially vulnerable users. Complete streets are roadways that safely and comfortably serve everyone, including motorists, bicyclists, pedestrians, transit and school-bus riders, delivery and service drivers, haulers and emergency responders.

Complete-street designs take into consideration the entire right of way, including the road and sidewalk, and the relationship to surrounding properties.

The complete street movement’s strategies for redesign streets is one piece of the solution to achieving Vision Zero. These principles align with the state of California’s efforts to change the way that transportation impacts are analyzed under CEQA (from Level of Service, which discourages congestion and can work against infill projects, to Vehicle Miles Traveled to better accommodate all road users).

Effective strategies include retrofitting poorly designed roads by adding (and widening) sidewalks, roundabouts, curb ramps, street lighting and bicycle facilities; narrowing streets; reducing crossing distances; and installing crosswalks and better bus stops to make walking and biking safer and more inviting. Redesigns help lower speeds and reduce points of conflict between motorists and between cars, pedestrians and bicyclists.

Reap the Economic Benefit of Safer, Complete Streets.

Many communities that have implemented changes to attract pedestrians and bicyclists have also reaped economic benefits (in addition to health and environmental benefits). Walkable streets generate more foot traffic for business, which increases sales-tax revenue. They have also been proven to increase property values. Walkable streets also encourage positive activity and increase the “eyes on the street” that have been shown to reduce crime.

The City of San Diego, La Jolla undertook a complete-streets plan along a two-mile stretch of La Jolla Boulevard in the Bird Rock neighborhood by reducing the number of lanes from five to two and redesigning five intersections that were previously stop- or signal-controlled with single-lane roundabouts. The “road diet” allowed the City to add diagonal parking on one side of the street, 10-foot landscaped medians, pedestrian crossings and plazas, and diagonal parking. Besides making the streets safer, the project triggered substantial revitalization of the adjacent businesses, and spurred substantial revitalization, including a number of new development projects. A survey of tax receipts among 95 businesses along the corridor showed a 20% boost in sales. Meanwhile, the 23,000 cars traveling on La Jolla Boulevard move through the corridor more quickly but at lower speeds because they don’t have to stop and start as they did previously.

Three years after the City of Lancaster’s downtown complete-streets redesign along a nine-block segment of Lancaster Boulevard was implemented, traffic collisions there fell by nearly one-third, and injuries among all users decreased by 67%. Moreover, The City’s $11.6 million public investment in the project sparked an estimated $125 million in private investment – and has generated more than $273 million in total economic output.

More than 40 new shops, restaurants, and businesses opened along Lancaster Boulevard, plus a new park and museum. Downtown property values increased 9.5%, and sales revenue is up 96% (compared to pre-construction revenue). More than 800 new jobs were created, and 807 new housing units were constructed or rehabilitated along or near the corridor.

Engage the Community.

Washington, DC engaged in a robust public process to draft their Vision Zero Action Plan. They hosted 10 community events, where nearly 2,700 people completed surveys to identify their top safety concerns (speeding cars, distracted drivers and travelers of all kinds ignoring traffic signals).

They developed an online, crowd-sourced Safety Map on which residents could identify hazardous locations and the conditions and behaviors they experienced there. This information on unreported crashes, near hits or other hazardous conditions are not reported in crash statistics. Combining user experience and aggregated crash data provides District of Columbia officials with a more detailed picture of safety to target street design and enforcement efforts. The nation’s capital has successfully reduced traffic fatalities by over 16% and injuries by over 20% from 2012-14.

They keep local residents engaged through a number of education and outreach efforts, including media campaigns, websites, news releases, social media, posters, brochures, videos, variable message boards and outreach teams.

The Future Is Brighter at Zero

The safety of our roadways affects all of us – from the personal loss many have faced to the impact on our taxes, the air we breathe, the prospects for our long-term health and mobility, the growth of our local economy, and the enrichment of our sense of place and security.

We can no longer consider traffic deaths as the inevitable cost of moving people around our communities.

The upswell in the adoption of state and local Vision Zero policies suggests we are experiencing a sea change in the way we think about designing our streets to ensure that the safety for all users comes first. That puts us on the right path toward more livable, healthier communities.

Resources to Learn More

- Vision Zero Case Studies and model resolutions: http://visionzeronetwork.org/

- League of CA Cities Vision Zero resolution: http://www.cacities.org/Resources-Documents/Policy-Advocacy-Section/Policy-Development/Annual-Conference-Resolutions/2016-Annual-Conference-Resolution-Final-Report

- More information on Complete Street Case Studies: https://www.legacy.civicwell.org/resources/community-design/#fact

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.