An Appetite for Change: Local Solutions and Stronger Goals to Reduce Food Waste

At a time when the landscape of California is shriveling up like a pumpkin in front of a house with a lazy dad, it seems especially unwise that farmers are pumping water into food that ends up being used as garnish for landfills.

– Comedian John Oliver

Two out of every five plates goes to waste: 40% of the U.S. annual food supply goes uneaten, according the Natural Resource Defense Council. To put a price tag on that, as a nation, we’re throwing out the equivalent of $162 billion each year, or roughly $1,500 a year lost on uneaten food for the average American family.

This food waste also incurs an environmental burden. About 25% of U.S. water supply goes to produce food that never gets eaten. In terms of air quality, this waste has a carbon footprint that matches the greenhouse gases from 33 million cars.

There’s certainly nothing funny about those numbers, but as comedian John Oliver aptly put it, “At a time when the landscape of California is shriveling up like a pumpkin in front of a house with a lazy dad, it seems especially unwise that farmers are pumping water into food that ends up being used as a garnish for landfills.”

A Global Shift

Government leaders in Sacramento, Washington and beyond are beginning to set goals to curb this wastefulness, and encourage local action by residents and businesses.

In September, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack and EPA Acting Deputy Administrator Stan Meiburg announced a goal to reduce food waste across the country by 50% by 2030.

“The United States enjoys the most productive and abundant food supply on earth, but too much of this food goes to waste,” Vilsack said. “Our new reduction goal demonstrates America’s leadership on a global level in getting wholesome food to people who need it, protecting our natural resources, cutting environmental pollution and promoting innovative approaches for reducing food loss and waste.”

The U.S. isn’t the only country recognizing the growing need to address food waste. France recently established a National Pact to cut food waste in half by 2025. The Consumer Goods Forum has matched that goal of reducing food waste through its industry membership of 400 food retailers and manufacturers across 70 countries by 50% by 2025.

Later this month, the United Nations will ask countries to adopt the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, one of which includes an element to cut “per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels” in half, and “reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses.”

California Goes After Organic Waste

At the state level, the California Air Resources Board last month announced a push to halt disposal of nearly all organic waste by 2025. The shift will likely require building new processing facilities, prod cities and counties to develop ways to collect it, and add an extra trash-sorting step before Californians drag bins to the curb.

During the 2014 legislative session, Governor Brown signed a law (AB 1826) that sets a statewide goal of recycling or composting 75% of all waste materials by 2020 and requires businesses to recycle their food waste beginning in April 2016.

Organic matter already makes up nearly half of California’s solid waste, and the total amount of solid waste is projected to reach 80 million tons by 2020. To reach our 75% diversion target, an additional 23 million tons will need to be recycled, reduced or composed in 2020. For the average Californian, that means translated to about 8 pounds a day.

Starting next year, cities and counties must have plans in place to manage the flow of commercial organic waste, including food scraps from restaurants. That mandate illuminates a broad underlying need: finding a place to put it.

Facility capacity and proximity are obstacles to our desire to prevent food and plant waste. Unlike most instances for recyclable materials as glass and metal, it can be more difficult and more expensive to transport organics because there are often no comparable facilities nearby – which also increases the vehicle miles travelled (VMT) and consequently the amount of greenhouse gas emissions.

Facilities scattered around the state can currently absorb only one-third to one-half of the 10 million tons of food and plant matter that end up in our landfills every year, according to CalRecycle. Just as troubling, the capacity of that infrastructure has barely budged in the past decade.

Growing Local Solutions, Building Capacity

Photo Credit: StopWaste.org

In Alameda County, large volumes of organic waste are already barred from entering landfills. Many businesses must recycle their food waste, and residents are provided special food scrap bins to separate organics from the garbage stream that goes to landfills.

The region’s waste managers say they have enough facility space for now, but they recognize that could change.

“We’re aware it could be a problem if the whole state mobilizes, so we’re going to continue to talk to people about facility development,” said Gary Wolff, executive director of StopWaste, Alameda County’s public agency for recycling and waste reduction, in a recent Sacramento Bee article.

Building waste-processing facilities such as composting sites entails navigating a complex regulatory process that includes specific siting rules and protections for local water supplies. It also costs money. Some of the funding could come from California’s new cap-and-trade program – $30 million has been allocated to CalRecyle this year.

Photo Credit: Hector Amezcua

Composting the waste is one option. Napa has the advantage of a county-owned composting facility. Davis, which collected 255 tons of food scraps from businesses and schools last year and is planning to have residents separate their food waste into special bins starting next summer, sends its organic matter to a private composting outfit in Lathrop.

Other cities and counties are hoping to use anaerobic digesters to convert the organic waste into biogas that can be used for fuel or electricity. That strategy reduces greenhouse gas emissions and potentially captures significant economic value in the process.

From developing composting ordinances to siting composting or anaerobic-digestion facilities, and from removing local barriers to food donations to changing municipal food-procurement policies, local governments will play a critical role in the future of food-waste prevention.

Fresno Adds Equity to the Food-Conservation Menu

The social tragedy in this epidemic of food waste is that millions of people are going hungry every day. It doesn’t make sense, and it’s not acceptable.

Source: Fresno Metro Ministry

While food is the single largest contributor to landfills today, one in six Americans doesn’t have a steady supply of food.

In the heart of the Central Valley, and the nation’s largest food-producing region, Fresno is now the second-most food-insecure metropolitan area in the U.S. Nearly one in four of its residents live without reliable access to a sufficient quantity of affordable nutritious food.

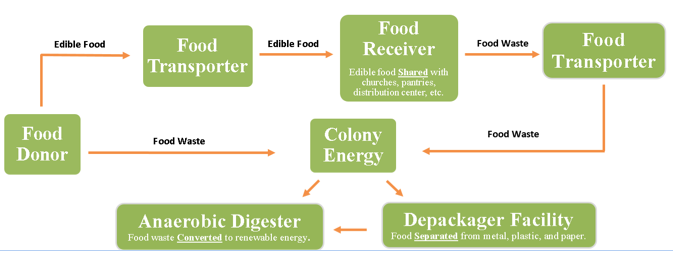

Fresno Metro Ministry has started “Food to Share,” a new community food systems project that seeks to divert edible food “waste” (before it becomes waste) from large sources – local supermarkets, restaurants, food distributors, hospitals, cafeterias, farmers’ markets, food-service facilities, growers and packers, gleanings and food institutions – and share it with churches, food kitchens, pantries and distribution centers. The food that isn’t edible will be diverted from the landfill and turned into renewable energy through a partnership with Colony Energy.

Fresno Metro Ministry says building an effective communication network among food donors and recipient organizations that can fully use rescued food to help feed disadvantaged communities is an essential part of “Food to Share.”

Early next year, their new website will let member donors instantly notify (via email and text message) food recipient organizations about available food, which they can claim electronically. The weight and type of food claims/deliveries will be documented for tax deductions and to verify emissions reductions. For example, one ton of rescued food equals 1.5 tons of reduced greenhouse-gas emissions.

The “Food to Share” initiative is supported by cap-and-trade funding through a grant from CalRecycle.

The Big Apple Targets Largest Food-Wasters

The new standard will apply to approximately 350 of the city’s biggest food generators, including large hotels, arenas and stadiums, and large-volume food manufacturers and wholesalers.

A 2013 New York City law (originally proposed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg) set about to solve the Catch-22 problem that confronts California’s local governments when establishing these new food-waste mandates: It’s hard to have a successful, wide-scale composting program for food scraps and yard waste if you don’t have sufficient composting facilities nearby that can accept the volume of these organic materials – and those facilities won’t get built or expanded until there is a reliable supply of organic waste.

To that end, the law directed the Sanitation Commissioner to evaluate the capacity of regional facilities that would accept food scraps and yard waste for composting, or similarly sustainable disposal processes like anaerobic digestion.

The commissioner’s analysis identified enough capacity – between 100,000 and 125,000 tons annually – in the region for processing the waste generated by the large businesses regulated under the City’s new proposal, which calls for 50,000 tons per year of food waste.

The program will ultimately encompass all significant food-waste generators in New York City. Mayor Bill de Blasio recently released the OneNYC sustainability plan with an ambitious zero-waste goal, which aims to reduce the amount of the city’s trash sent to landfills by 90% by 2030.

The NYC Sanitation Department is already conducting a separate pilot project that collects food waste for composting from more than 100,000 households and 700 public schools across the city.

The proposal must still go through a formal rule-making proposal this fall before it is adopted in final form.

SF Sets the Table for Zero Waste by 2020

In 2002, San Francisco adopted a citywide goal of diverting 75% of its waste from landfills by 2010 and set a zero-waste standard by 2020.

Photo Credit: Justin Sullivan/Getty

San Francisco’s Department of the Environmentstarted by targeting the city’s hotels and restaurants, which produce a great deal of organic waste.

“We started with a test hotel, the Hilton, which serves 7,500 meals a day, and we set up a simple system: collection carts containing recyclable or compostable material cost much less a month on the bill than those containing non-recyclable waste,” said Jared Blumenfeld, the former department head and now the EPA’s Pacific Southwest regional administrator, in a 2014 Guardian article.

“If you recycle and compost all your waste, you will need fewer, or much smaller, trash carts. And you’ll save money,” he added.

The system was a success. In the first year, the Hilton saved $200,000, and the approach was extended to the whole catering industry in the area. It was also made available to residents on a voluntary basis.

“In four years, we went from 42% recycled waste to 60%,” Blumenfeld said.

Building on this track record, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed the Mandatory Recycling and Composting Ordinance in 2009, requiring all commercial and residential consumers in the city to separate recyclables, compostables and landfill-bound trash.

Read the policy.

Under the new ordinance, each house or building received a detailed bill, which could be cut by reducing the use of trash cans and shifting waste to those set aside for composting. These rules are backed by regular checks. Those who fail to comply receive warnings, followed by fines ranging from $100 to $1,000.

“That was the most controversial measure,” Blumenfeld admits. “We were accused of setting up an environmental police force. We spent a long time explaining that there was no question of that, and that everyone stood to gain. If we’d made this mandatory straight away, it wouldn’t have worked. It had to be gradual.”

San Francisco’s zero-waste efforts have had a tremendous impact over the last two decades. Mandatory recycling and composting have increased organics collection 50% to more than 650 tons a day – more than any composting program in the country.

The effort was worth it. In 2010, San Francisco achieved a 77% waste-diversion rate, and has since topped 80%. Every day, approximately 650 tons of organic waste is recovered and sent to the Vacaville facility, which now produces compost highly prized by farmers.

Economic, Environmental and Social Benefits

The imperative for closing the food-waste loop has social ramifications.

Last year, more than 48 million Americans lived in food-insecure households (14% of all households), including more than 15 million children. Perhaps not surprisingly, households that had higher rates of food insecurity than the national average included households with children, black and Hispanic households, and seniors (9% of all seniors in 2013).

As we must find innovative strategies to mitigate and adapt to climate change, eliminating food waste also offers many environmental benefits.

“Landfilled food and other organic materials produce methane, a major contributor to climate change,” said Assemblymember Wesley Chesbro, who authored California’s legislation (AB 341 and AB 1826) that set the 75% target and the 2016 mandate for local jurisdictions to implement organic waste recycling programs. “Methane is a greenhouse gas that traps 21 times more heat than carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas created by the burning of fossil fuels.”

Most food-waste efforts also carry economic advantages, in both reducing costs for residents, businesses and local governments and generating new revenue streams that create new jobs and businesses.

“In the near future, the concept of letting millions of tons of plant trimmings and food scraps rot in a landfill will be seen as an antiquated notion, similar to the 19th-century practice of dumping waste directly onto our city streets,” said Nick Lapis, legislative coordinator for Californians Against Waste. “We are far too advanced, in terms of technology and our awareness of climate change, to let this material rot in landfills and generate enormous amounts of methane, especially when we know we can turn this so-called ‘waste’ into valuable compost and a source of bioenergy. The recycling of cans, bottles and other materials has been a boon for our environment and economy, and recovering organic waste will be no different.”

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.