Small Space, Large Innovation: Accessory Homes

The hottest amenity in real estate these days is an in-law unit, an apartment carved out of an existing home or a stand-alone dwelling built on the homeowner’s property.

– Wall Street Journal, November 2014

Last month we highlighted communities (from Sonoma County to Austin) using “tiny houses” to shelter homeless residents. With housing affordability a growing challenge for local economies across the country, tiny houses are gaining momentum because they offer solutions for a number of income and demographic groups, ranging from teachers and service workers to seniors and single-parent households.

Several factors are influencing the rapid shift in the housing market:

Households evolving

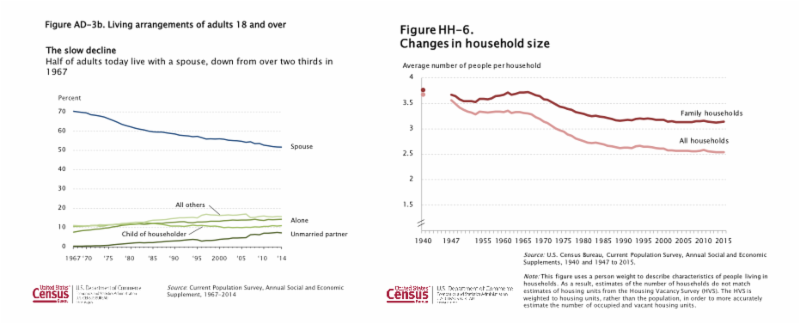

For decades, homes have been built in large measure to accommodate the “traditional” family of two parents and two children. The reality is that most households no longer reflect this make-up. Fewer households are comprised of married couples, and the average household size is decreasing (see charts below).

Only 24% of California’s population fit this model, according to the 2010 state census, and yet 60% of our housing stock is single-family detached homes for this “traditional” family. However, household size is decreasing. So we are dedicating a significant portion of our communities to large homes that are not filled (and continue to build detached single family homes) while we have gaps in housing units available that cater to the rest of the population: single-parent families, couples without children, empty nesters, retirees, young professionals and individuals of all ages – pushing too many people further from their jobs.

What young and aging people want

The gap between the current housing supply and the new demand will likely grow as California’s two largest demographic groups (Millennials and Baby Boomers) have different needs than their age counterparts of past. Young professionals (25-34 year olds) rely on rental housing for longer periods than previous generations due to low wages, the high cost of living, and outstanding student debt (HCD Housing Update 2012).

The number of seniors will nearly double in the next 20 years, from 4.3 to 8.4 million, with little time to develop the necessary institutional housing (HCD Housing Update 2012). Baby Boomers will live longer than previous generations, and the vast majority of them want to stay in their homes and age in place (HCD Housing Update 2012), a preference that could be financially out of reach for many seniors.

Affordability a problem for most people

The average home price in California ($440,000) is about 2½ times the national average, while California’s average monthly rent ($1,240) is about 50% higher than the U.S. average, according to a March 2015 report by the Legislature’s independent analyst.

Those high prices are largely driven by a slow pace of construction in the state’s major coastal markets, where demand for homes is highest and prices are bid up. Between 1980 and 2010, for example, new home construction in the state’s coastal metro areas increased by 32%, compared with 54% nationally. In Los Angeles and San Francisco, the supply of new housing grew even more slowly, by about 20%.

As a result, a larger portion of Californians’ incomes goes toward housing, which has increased the supplemental poverty measure, a key gauge of poverty that takes housing costs into account. California’s poverty rate by this alternative measure is 23.4%, the highest in the country.

High housing costs have also led to delays in home purchases, more debt, longer commutes and a higher propensity toward living in crowded conditions, the report found. The overwhelming majority of households in California could not afford to rent or buy their current home if they were entering the housing market today.

This is creating a housing crisis because teachers, caregivers and other vital workers can’t afford housing in the communities where they work, particularly in affluent coastal communities.

Increasing Housing and Homeowner Flexibility

Accessory Dwelling Units

Since 2000, the Local Government Commission has been encouraging local governments to allow for accessory dwelling units as a way to increase housing options without government subsidies. Accessory units expert Patrick Hare estimates that one out of every three single-family homes, or about 15 million homes in the U.S., have enough space to accommodate an accessory unit.

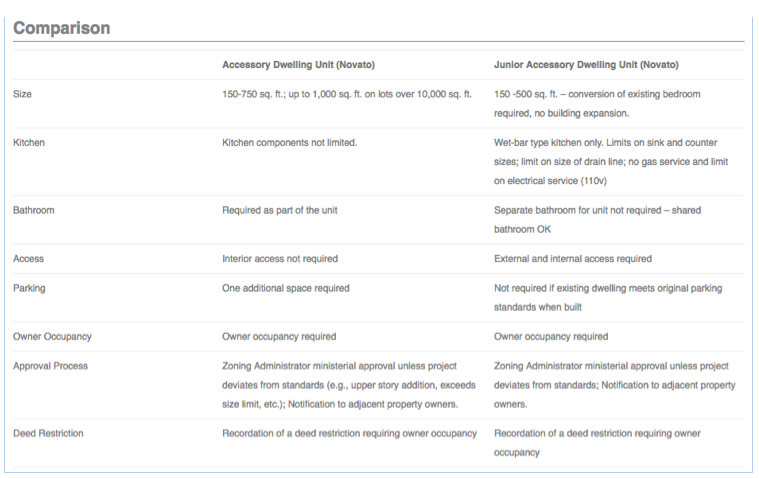

Accessory dwelling units (ADU, sometimes called “granny,” “in-law” or secondary units) are allowed in all California jurisdictions, but creation of legal ADUs is often constrained by local zoning requirements and fees. Some cities have changed their codes and standards to address ADUs.

The City of Santa Cruz adopted an ADU ordinance in 2003 that set forth regulations for the location, permit process, deed restrictions, zoning incentives, and design and development standards for ADUs. Development fees are waived for ADUs made available for low- and very-low-income households.

Santa Cruz also established an ADU development program with three major components: technical assistance, a wage subsidy and apprentice program, and an ADU loan program. As part of the technical assistance program, the City published an ADU Plan Sets Book that contains design concepts developed by local and regional architects. Homeowners can select one of these designs and receive permits in an expedited manner.

It also offers an ADU Manual, which provides homeowners with information on making their ADU architecturally compatible with their neighborhood, zoning regulations relevant to ADUs, and the permitting process. Santa Cruz has seen an average of 40 to 50 ADU permits approved every year since the start of the program, attributed primarily to zoning changes that were adopted to facilitate development of ADUs, such as the elimination of covered parking requirements.

In Oakland, the City Council is considering changes in its secondary-unit rules to create much-needed new affordable housing by amending the rules on building secondary units on property near transit lines and hubs in many neighborhoods. The proposed changes would eliminate an off-street parking space requirement of one space per unit of housing and ease setback requirements for secondary units, while reducing to 700 square feet the maximum size of the unit.

The measure, slated for a final reading next month, would allow Oakland residents who live in communities no more than a half-mile from a BART station, Bus Rapid Transit line or major transit hub to more easily build a secondary rental unit on their property or convert an existing structure into a living space that can be rented.

Junior Second Units: Adding A Unit inside the Home

Despite the benefits of ADUs, they can be very costly to permit and comply with regulatory requirements. In Marin, for example, it costs approximately $15,000 to $32,000 to permit and pay for the connection fee for an ADU, $10,000 for parking, and another $10,000 to install a sprinkler to meet fire safety requirements. Construction could cost as little as $10,000 but with the additional $35,000 to $52,000 to meet local requirements, many people are priced out.

“The hottest amenity in real estate these days is an in-law unit, an apartment carved out of an existing home or a stand-alone dwelling built on the homeowners’ property,” according to a November 2014 Wall Street Journal article. And for good reason: a Zillow study found that the listing prices of homes with in-law units in major cities were 60% higher than the listing prices of homes that didn’t have units. View a graphic on the Junior Second Unit lifecycle.

There is a growing movement to look at options using the existing footprint of a home. Junior Accessory Dwelling Units (JADUs) are a special type of ADU that repurpose spare bedrooms in existing homes (rather then build an additional separate structure) to create a small efficiency apartment up to 500 square feet with a separate entrance. These units are subject to less strenuous zoning regulations and fees with the logic that all of the water, fire safety and parking, etc. for that bedroom has already been accounted for in the permitting of the home.

That said, many communities have still required those additional fees until recently. A number of Bay Area communities are reducing fees to increase the availability of additional housing units in a way that doesn’t change the fabric of existing communities where large housing complexes are often very financially and politically difficult to develop.

It’s also a way to keep people in their houses who experience life events, such as a job loss, divorce, injury, death in the family or retirement – that change a homeowner’s ability to make their mortgage payment.

In four Bay Area cities, you can now – or soon will be able to – build Junior Accessory Dwelling Units. Tiburon and Novato passed their ordinances in 2015. This month, the San Rafael City and Fairfax Town Councils approved Junior Second Unit (JSU) ordinances that will soon go into effect.

The challenge is the costs that many cities charge. Because all of the water, waste and energy, road use and parking for existing bedrooms has already been accounted for in the original permit for the home, no additional utility service, parking or infrastructure should be required for the development of JADUs. No fire sprinklers or fire attenuation should be required for JADUs because the interior door leading to the main living area remains.

Last year the City of Novato passed an ordinance permitting junior accessory dwelling units. The City and the Novato Fire Protection District reduced or eliminated their fees and requirements. In April 2015, the North Marin Water District eliminated the $10,000 water connection fee; and in May 2015, the last potential hurdle was removed when the Novato Sanitary District Board unanimously approved a sewer service fee reduction from $8,990 to $40 for JADUs. The end result is that 98.5% of the fees for JADUs were cut, when compared to traditional accessory dwelling units.

- Fees for a traditional accessory dwelling unit of less than 500 square feet: $27,507

- Fees for a junior accessory dwelling unit of more than 500 square feet: $414

For more information on JADUs and a model local ordinance: Lilypad Homes

Community Investments that Change Lives

A home is most people’s largest, most personal investment. Accessory Dwelling Units allow homes to be flexible enough to meet a homeowner’s changing needs. At a time when many communities are facing an affordable housing crisis, traditional tools to build housing (such as redevelopment agencies) are no longer available and public funding is limited local governments should seriously consider measures to encourage Accessory Dwelling Units that can keep community members in their homes, provide more housing options and reduce travel time and associated environmental impacts.

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.