California’s housing affordability crisis is not only costly for people renting or buying homes, it weakens California’s economy as a whole.

Solving the Affordability Crisis: Practical Strategies to Build More Housing

Solving the Affordability Crisis: Practical Strategies to Build More Housing

Housing shortage costs the California economy between $143 billion and $233 billion per year.

– McKinsey Global Institute

California’s housing shortage is not only costly for people renting or buying homes, and devastating for our most vulnerable residents, it also weakens California’s economy as a whole. A 2016 report by the McKinsey Global Institute titled “A tool kit to close California’s housing gap: 3.5 million homes by 2025” calculates that housing shortages statewide cost the California economy between $143 billion and $233 billion per year. This conservative estimate accounts for impact on consumption, lost construction activity and costs to address homelessness – it does not take into account broader costs to health, education and the environment.

- Households that spend a large share of income on rent or mortgage payments have less money to spend on other things, to the tune of an estimated $53 billion to $63 billion in reduced consumption per year.

- California’s housing shortage is also a lost opportunity for the construction industry – the report estimates that lost construction activity costs the state economy $85 billion to $165 billion annually.

- California spends $5 billion a year to provide shelter, emergency-room visits, policing, mental-health interventions, and other services to our homeless populations.

The housing affordability problem is not just a big-city issue – it affects both urban and rural communities.

Of the 5.9 million Californian households unable to afford the cost of housing, approximately 62% live in the inner San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim region.

Meanwhile, in the rural Santa Cruz-Watsonville metro region, 57% of households are also unable to afford the cost of housing. In Salinas and Clearlake, another rural area, the share is 50%. In Merced, housing prices have risen four times as fast as income.

In high-income areas such as Silicon Valley and San Francisco, housing prices have climbed at double the rate of income, making more homes less affordable for more people.

Given that nearly half of California’s households cannot afford the cost of housing in their local market, it is not an understatement to say that we are facing a statewide affordability crisis. In every metropolitan statistical area at least 30% of households (as high as 60% in some regions) cannot afford the cost of housing.

Higher demand plus insufficient supply has inevitably pushed up California’s real-estate prices and created an affordability crisis in communities throughout the state. Today, California ranks 49th out of the 50 states in the number of housing units per capita.

The McKinsey Global Institute report estimates that California must build 3.5 million housing units by 2025 to satisfy pent-up demand and meet the needs of its growing population.

On the positive side, there is room to build more housing. The report identifies 5 million new units of various kinds could be built in high-demand towns and cities throughout California. Some would be single-family homes on small lots; some would be “accessory dwelling units,” such as converted garages or new backyard cottages; and others would be multifamily infill apartment buildings or condos.

To address homelessness, economic pressure on both low-income and middle-class families, growing threats of displacement, and other challenges associated with the state’s affordability crisis, California needs to build all of these housing options.

Infill Multi-Family Development

The report mapped specific lots, parcel by parcel, in places such as Los Angeles, San Francisco and Fresno, and identified room for a quarter-of-a-million new units on urban land already zoned for multifamily development but sitting vacant. There are several strategies to implement this type of housing:

- Inventory and publicize vacant sites in an accessible format. OppSites is one example of how cities are publicizing sites for investment.

- Incentivize owners to bring vacant sites to market. Cities can impose a higher marginal tax rate on idle urban land, or assess vacant sites as if they contained buildings and improvements comparable to surrounding plots. For example, Harrisburg and 20 other Pennsylvania cities do split-rate property tax – dividing property assessments into two parts, in which the value of the land and the value of the buildings is taxed higher than improvements in the actual buildings. That means developers can’t simply sit on land, unless they want to foot the bill for the extra taxes.

- Accelerate land-use approvals for housing developments on vacant urban land that is already zoned for multifamily development.

- Provide incentives for infill development on vacant sites, such as property-tax holidays or partial public funding for infrastructure upgrades.

Single-Family Smart Growth

There is also room for more than 600,000 “smart-growth,” affordable single-family homes on undeveloped land near jobs and transit. The McKinsey Global Institute report mapped high-growth counties – including Contra Costa, San Bernardino and Sacramento – to identify building sites that would minimize sprawl, cut highway gridlock, and preserve open space and farmland. The new homes would be within five miles of a public transit hub, or within 20 miles of regional job centers.

Implementation strategies for this type of housing growth might include:

- Rezone station areas for higher residential density, paving the way for private investment.

- Accelerate land-use approvals in “priority”-designated transit areas.

- Finance station-area infrastructure and housing through tax increment bonds. In November, a number of communities successfully passed bond measures for affordable housing, including the City of Los Angeles’ $1.2 billion bond for low-income housing, Santa Clara County’s $950 million affordable-housing bond and Alameda County’s $580 million bond for low-income residents through housing programs for homeowners, renters and the homeless.

Transit-oriented Development

The biggest opportunity is transforming the areas around California’s transit stations into housing hubs. The state could build up to 3 million new housing units within a half-mile of high-frequency transit — transforming suburban station areas into walkable, mixed-use villages and adding high-rise urban housing in big-city cores.

Implementation strategies for more TOD:

- Reduce barriers to the creation of accessory dwelling units that can provide extra income to help homeowners stay in their homes and increase the number of affordable housing units. Cities like Oakland and Berkeley have changed their local zoning codes to help homeowners create accessory dwelling units. Three state bills passed this year that go into effect in 2017 (B. 1069, A.B. 2299, A.B. 2406) make similar changes at the state level, including waiving off-street parking requirements, expediting approvals and permitting, and linking fees to the size of units.

S.B. 1069 and A.B. 2299 both support the building of “accessory dwelling units” (ADUs) by requiring cities to allow ADUs by right in certain areas and reducing costs by preventing water and sewer agencies from charging hookup fees for ADUs built within an existing house or an existing detached unit on the same lot and prohibiting parking rules for ADUs located within a half-mile from public transit, or units that are part of an existing primary residence. A similar bill, A.B. 2406, prohibits local ordinances from requiring additional parking or utility hookup fees as a condition to grant a similar permit for “junior accessory dwelling units,” which are extra units built within the existing walls of a house.

- Proactively encourage homeowners to create accessory dwelling units and co‑living spaces. For example, San Mateo County is using geospatial mapping to identify homes that have room to add an accessory dwelling unit, and is proactively approaching those homeowners to encourage the construction of these new housing options.

- Provide an amnesty path for unregistered accessory dwelling units. By one estimate, illegal accessory dwelling units represent up to 8% of San Francisco’s housing stock. Legitimizing these units would boost building-code compliance and raise property-tax revenue.

Widely Applicable Strategies

There are also several tools to help encourage and build all three of these types of new housing:

- Accelerate development approvals for “priority” projects, including affordable housing, infill and transit-oriented development. It takes six months on average to approve relative simple projects in California, and three years on average for more complex projects. Protracted land-use decision-making and litigation are costing Californians well over $1.4 billion a year, and are a major cause of California’s housing under-supply.Redwood City and Fresno have instituted new zoning codes that are clear and comprehensive; and they have proactively completed environmental impact reviews to establish where and how development can proceed. If a proposed project checks off all the boxes specified in one of these city’s zoning codes, it can be approved over the counter, with no need for additional review.

- Reduce impact fees for high-priority projects. California’s impact fees are approximately three times higher than average fees in other states. Communities could defer or waive fees for projects that help meet affordable housing and sustainability goals.

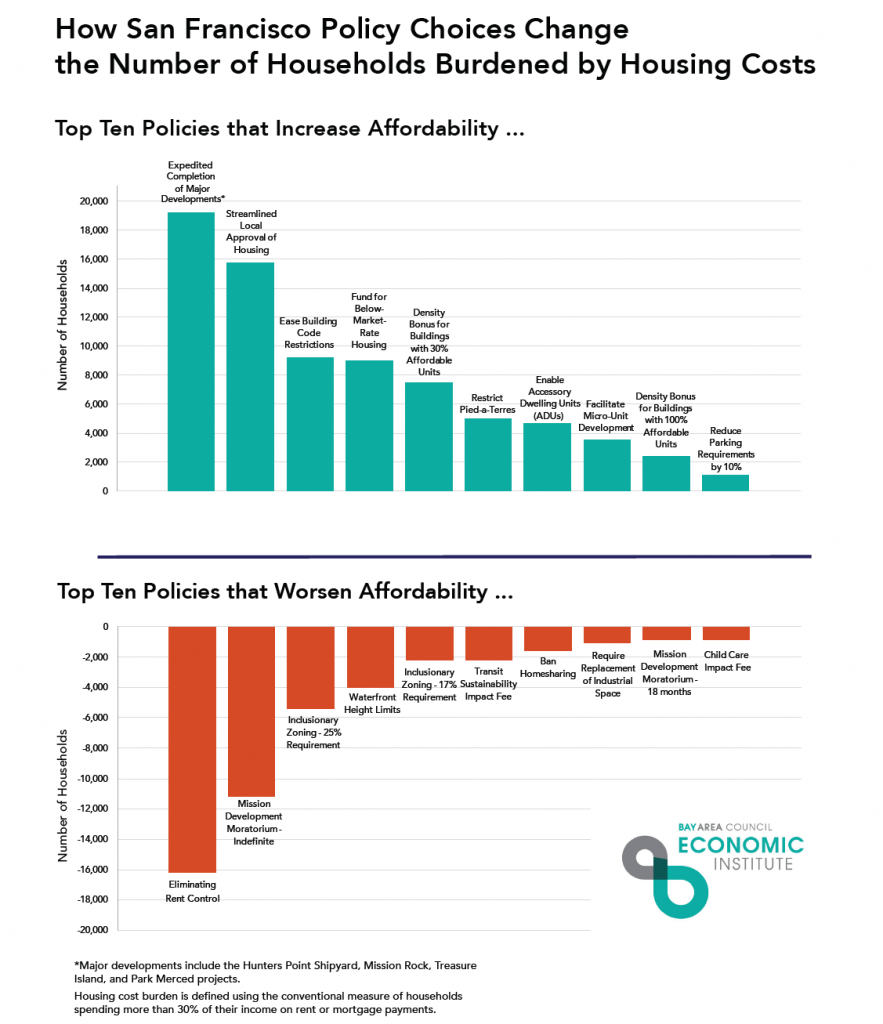

- Provide density bonuses. Cities can allow projects that include a certain percentage of affordable units for low- and middle-income households would have been able to build more residential units than currently allowed under existing zoning regulations.In June 2016, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved an Affordable Housing Bonus Program that provides a density bonus for buildings with 100% below-market-rate units. Under the legislation, developments offering units affordable to those earning less than 80% of the area median income (AMI) can obtain a 30-foot increase in height bonus, or three stories.

- Reduce parking requirements. Reducing parking requirements by one space can reduce housing construction costs by $38,000.

- Allow micro-units. In 2011, San Francisco passed legislation to enable the construction of “micro-units,” or efficiency dwelling units. The legislation allows for units as small as 220 square feet comprised of 150 square feet of living space, plus a bathroom and kitchen. Other high-demand housing markets, including New York, Boston, Portland and Seattle, have also made zoning changes to allow for micro-unit development. Allowable sizes average approximately 350 square feet. Micro-units generally rent for about 20% to 30% less than a regular-sized unit. While examples of micro-unit development at scale do exist, their growth has yet to accelerate on a wider scale due to parking requirements, unit-mix requirements and indoor common-space requirements (zoning changes which are conceptually easy enough to make).

Restrict non-primary residences in regions with high housing costs. Denmark, Norway and Switzerland all limit second-home ownership in some way, while Australia limits foreign ownership, and Vancouver recently adopted an additional 15% property transfer tax for foreign buyers.

Political Capital, Financial Investments and Local Incentives Required

California’s housing crisis is not just affecting housing prices but also traffic congestion, clean air and the future growth of individual local economies. Delays in increasing the housing supply will continue to drive people further and further out of town, in search of rents they can afford. For rents to come down, we need to build both market-rate and affordable housing for all income levels. These new units need to be really affordable for residents who are most desperately in need and for those who are doing relatively ok – and everyone in between.

This reality means the solution to California’s affordable housing crisis will require a comprehensive, all-in plan. State leadership is needed to increase funding and financing for affordable housing and incentivize good-faith local actions to expand the housing supply. At the community level, local governments can pull a number of policy levers to increase all types of housing to support affordability at all income levels and prevent displacement, especially for our most underserved and vulnerable residents.

Resources

McKinsey Global Institute report on closing California’s housing gap (October 2016)

Bay Area Council Economic Institute Report on Solving the Housing Affordability Crisis: How Policies Change the Number of San Francisco Households Burdened by Housing Costs

Local Government Commission Newsletters

Livable Places Update

CURRENTS Newsletter

CivicSpark™ Newsletter

LGC Newsletters

Keep up to date with LGC’s newsletters!

Livable Places Update – April

April’s article: Microtransit: Right-Sizing Transportation to Improve Community Mobility

Currents: Spring 2019

Currents provides readers with current information on energy issues affecting local governments in California.

CivicSpark Newsletter – March

This monthly CivicSpark newsletter features updates on CivicSpark projects and highlights.