Saving Borrego’s Lifeblood

This will be a year to remember in California’s history – not only due to the COVID 19 pandemic and subsequent economic devastation – 2020 marks the beginning of a new era in the state’s approach to water management.

Despite California’s pride in being at the cutting edge, we were the last state in the nation to require comprehensive groundwater management. We have followed a continuous trend of groundwater overdraft for more than 50 years – with more water being pumped out of the ground than is naturally recharged. As agriculture, industry, and residential users raced to the bottom of the aquifer, it was unclear how water managers would balance these competing interests and ensure a reliable long-term water supply.

All that changed in January, when recently-formed Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) representing the state’s high-priority groundwater basins, submitted forty-six groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) to the Department of Water Resources. These GSPs are an important milestone of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, legislation passed in 2014, at the height of California’s most severe drought on record.

Borrego’s Groundwater Problem

Borrego Springs’ only viable water source is a large aquifer under Borrego Valley; it has long been accepted that the aquifer’s water collected over millennia and is being pumped at a rapid pace by recent generations. What farmers, developers, business owners, and residents never agreed upon was how much water was actually available, and how long it would last.

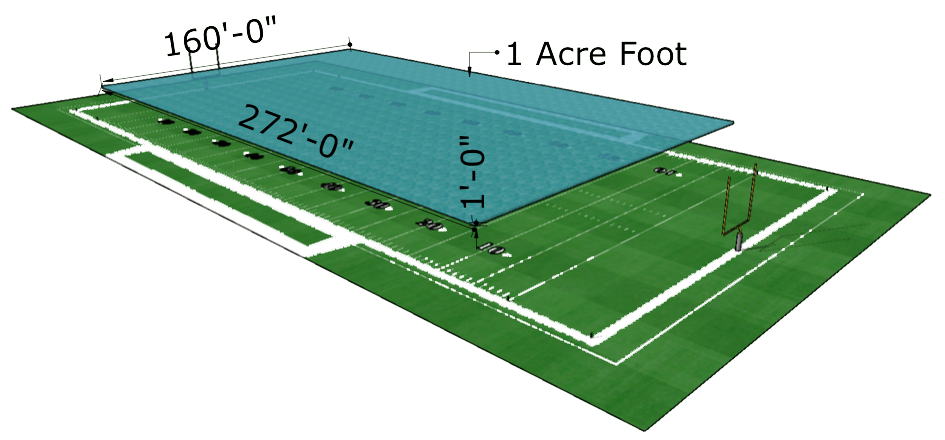

This debate should have ended with a 1982 United States Geological Survey (USGS)[2] hydrologic report commissioned by San Diego County. The USGS report determined that the aquifer’s water recharged at a rate of roughly 6,000 acre-feet per year; and there was likely 3 million acre-feet of water in the aquifer at that time (to envision an acre-foot, imagine a football field filled with 12 inches of water). For decades, however, the report was dismissed, diminished, and questioned by pumpers who did not want to believe it. It became a figurative football, as each stakeholder interpreted the data for their own interests and estimated how long they thought the water would last. The bottom line, though, is that the aquifer was already in overdraft.

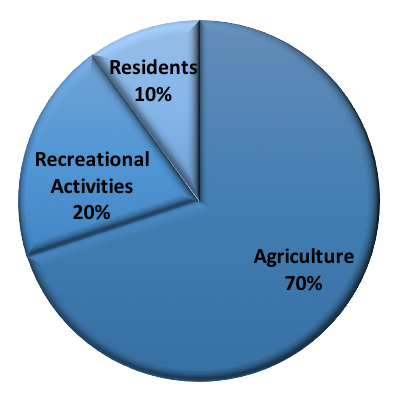

Of Borrego’s water supply, agriculture uses roughly 70%, recreational activities (predominantly golf courses) use about 20%, and municipal residents/businesses are left with the remaining 10% of available water.[3] This pattern emerged under pre-SGMA California Water Law, in which landowners had the right to pump as much of the water beneath their property as they liked; there was no established limit on how much water any one entity could use. This setup benefited farmers, whom we depend on to grow the food that sustains California and our economy. It allowed them to grow crops favorable to market demands and local weather conditions, but not necessarily favorable to available water supply. Some question, for example, whether the grapefruit Borrego Springs is known for holds as much value as the water they take to grow; and whether farmers should be allowed to make money off of water the community depends on without adequate protections for the longterm sustainability of the aquifer. This is exactly the issue SGMA was designed to address.

Disagreement between the three primary user-groups continued through the 1990s, with little action toward actual groundwater management. Some community leaders hoped a free market solution would eventually prevail: as the aquifer level dropped and water became more difficult to pump, it would become too expensive to grow crops and the farmers would leave. This hope had two flaws: 1) agriculture provided jobs for many local residents, and 2) if water is too expensive for farming, will it also become too expensive for everyone else?

SGMA – Déjà vu for Borrego’s Water Woes

The 2014 passage of SGMA was déjà vu for many long-term Borrego residents. Nearly 20 years earlier, AB 3030, also known as the Groundwater Management Act, enabled the Borrego Water District (BWD) to develop Borrego’s first Groundwater Management Plan (GMP). Published in 2002, Borrego’s GMP[4] discussed the need for restrictions, but failed to establish a deadline for meeting proposed reductions, nor did it hold authority to charge pumping fees or penalties. Unlike the 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, this legislation had no teeth.

Recognizing that Borrego’s growth was limited by an unregulated aquifer, Borrego Water District sought other methods of securing water for the community’s future. As the Valley’s sole water supplier, it was up to BWD to find a solution. The Water District considered many proposals, including importing Colorado River water, offering Borrego’s aquifer as a storage reservoir to neighboring areas in exchange for using some of their water, and drilling a well in nearby Clark Dry Lake. Feasibility study after study determined each project to be excessively costly, politically infeasible, and many required piping water through protected state parkland or risking Borrego’s water quality by mixing with inferior water sources. Despite BWD’s laudable efforts, no viable alternatives emerged for Borrego. Competition and distrust between water users continued to fester.

The 2002 Regional Water Management Planning Act (SB 1672) offered new hope for Borrego’s water problem. However, after 2+ years of facilitated negotiations between BWD, San Diego County, and community stakeholders, all Borrego had to show for its efforts was continued animosity between water users and two failed attempts at developing a voluntary (non-regulatory) Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) Plan. The failed IRWM process highlighted that the community could not address its water problems without first building trust between the basin’s major stakeholders.

By 2012, Borrego Water District appealed to the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) for help, and DWR provided a facilitator to convene stakeholders and improve Borrego’s 2002 Groundwater Management Plan. Thus formed the Borrego Water Coalition (BWC), a group of groundwater pumpers representing agriculture, recreation, businesses, BWD, the school district, the county, and the state park. It should be noted that the BWC lacked a community resident representative. While some of the representatives were indeed Borrego residents, their position on the BWC was to represent their special interest. Therefore, the BWC was not accountable to the community more broadly. The Borrego Water Coalition, which adopted the motto “Water for the Future,” met as a closed group. This was done to engender honest conversations and build trust between the represented user groups, but had the negative effect of continuing to exclude the broader community. Awareness of comprehensive groundwater legislation being debated in Sacramento during this time motivated the Coalition to reach agreement and align their plan with the anticipated Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

Emergence of the Stewardship Council

The closed-door secrecy of the Water Coalition, however, fostered suspicion within the broader community. It was clear to many that a community-based forum for addressing Borrego’s most pressing issues, such as water, air quality, land-use, and economic development, was necessary. The Borrego Valley Stewardship Council (BVSC)[5] formed in 2014 to respond to these interconnected challenges and convene diverse community voices in matters affecting the future of Borrego Springs. The goal of the Stewardship Council is to enhance the viability of a vibrant, resilient desert community. Geotourism was the chosen vehicle to achieve this goal, codified in a Geotourism Charter signed by 17 public agencies, businesses, non-profit organizations and volunteer associations. For the first few years, the BVSC existed as a loose network of partners with no official governance structure, supporting initiatives undertaken by its signatories. For example, BVSC supported the Borrego Village Association (BVA) – whose mission is to promote a thriving, attractive community and enhance tourism – to develop an Interpretive Host Program that trains current and future tourism workers to elevate the visitor experience. This program has since expanded to include credited coursework at Borrego Springs High School for students to learn the art of natural resource interpretation and become Certified Interpretive Guides. This integration of protecting natural resources, enhancing tourism, and providing employment pathways for local residents exemplifies the BVSC’s mission in action.

The Stewardship Council became more directly involved in Borrego’s water sustainability when SGMA passed into law in September 2014. As a “high priority” basin in “critical overdraft,” Borrego was one of over 140[6] basins required to form a Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) by the earlier deadline of June 30, 2017. Thanks in part to the work of the Borrego Water Coalition, Borregans were ahead of the curve in forming their GSA and starting to develop their Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP). By 2017, San Diego County and BWD were designated the Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) as a joint powers authority. They in turn convened a 9-member GSP Advisory Committee, populated by former members of the Borrego Water Coalition, and including representatives from the Borrego Springs Community Sponsor Group (the official liaison between Borrego Springs and San Diego County) and the newly formed Borrego Valley Stewardship Council.

Coming to Terms with Borrego’s Water Future

Over the next two and a half years, the GSP Advisory Committee labored over the development of the GSP along with BWD, San Diego County, and DWR grant-funded facilitators and consultants. This group’s herculean task was the creation of a plan that reduces annual pumping of Borrego Valley’s aquifer to its 5,700 acre-feet sustainable yield by 2040. That’s a 75% water use reduction over a twenty-year period; arguably the most dire condition of any groundwater basin in the state. Borrego’s GSP development process certainly faced its fair share of challenges. Thanks to a grant from the Department of Water Resources, though, the Advisory Committee was able to conduct extensive community engagement. And unlike many GSAs, Borrego’s Advisory Committee actually had some impact on decisions throughout the process.

The region was receiving significant bad press about its water situation, positioned as a “dying community,” “drying up in the desert.” While water is indeed the greatest limiting factor in Borrego’s potential and resilience, water is inextricably linked to land use, economic development, and public health. Borrego wants to prove these headlines wrong; reidentify itself as “a phoenix rising from the ashes.” The Borrego Valley Stewardship Council, with support from the Local Government Commission, began exploring integrated planning in concert with the SGMA implementation process, in order to redefine Borrego Springs and its future.

Integrated Planning for Long-term Resilience

Through a combination of local, regional, and statewide philanthropic funding,[7] LGC worked with the Stewardship Council and representatives of the broader community to educate stakeholders on the benefits of integrated planning. Together they convened a cohort of local leaders and developed a scoping proposal[8] for a Borrego Springs integrated watershed-scale master plan that would align groundwater management, land use planning, economic development, public health, and community resilience – to chart a course for a thriving future Borrego Springs. The Borrego Water District and the Anza Borrego Foundation, both BVSC signatories, jointly managed a CivicSpark Fellow to develop an action plan for BVSC to more thoroughly engage the community around the integrated planning process. Simultaneously, LGC supported the Stewardship Council and other community leaders with broader engagement in the GSP development process and reviewing Borrego’s draft GSP.

Released on March 22, 2019, the Draft Groundwater Sustainability Plan[9] for the Borrego Valley Groundwater Basin was the first in California to be released, and one of the state’s few draft plans released in its entirety – considered a best practice by many SGMA practitioners and community engagement specialists. Although SGMA does not require any public review prior to GSP adoption, the Borrego Valley GSA provided a 60-day comment period on the Draft GSP, again considered by many to set a precedent for other GSAs across the state. It seemed the Borrego Valley GSA was on the right track; the Stewardship Council and other community members were excited at the prospect of serving as an example to other basins across the state – another opportunity to disprove those negative headlines. Yet soon after the draft plan was released, distrust between basin pumpers bubbled up once again.

11th Hour “Friendly” Adjudication

Public questioning during the GSA Advisory Committee convening and data gathering process made some groups defensive and less cooperative in the public planning process. While BWD was under pressure from the basin’s major pumpers to approve private negotiations, San Diego County informed BWD of the County’s intention to withdraw from the GSA as soon as the plan was finalized. Apparently the major pumpers did not want to be accountable to the public, and the County did not want to be responsible for any implementation. BWD could not serve as a viable GSA under SGMA without the County’s participation because the county is the region’s sole land-use authority. These two factors culminated in BWD approving private negotiations. Anticipating that the GSP would soon be replaced by the stipulated agreement most of the committee members had not yet seen, the GSA Advisory Committee voted to accept the draft GSP. They did so as an act of solidarity with their community and to acknowledge the hard work of BWD and others in developing the GSP. They also hoped the GSP would eventually become part of the stipulation agreement. Two of the basin’s largest agricultural pumpers, parties to the private negotiations, declined to accept the GSP.

In the 11th hour, attorneys for the major pumper groups (agriculture, golf & parks, and municipal) released a stipulated agreement with no opportunity for public input.[10] The stipulated agreement would pursue a “friendly adjudication” of the Borrego basin, rather than moving forward with the publicly-developed Groundwater Sustainability Plan. Many Borregans, including GSA Advisory Committee members, were affronted by the closed-door nature of the stipulated agreement, and the 3 years of hard work dedicated to the public process toward a community-driven plan that was now being passed over. Statewide SGMA practitioners and community advocates were also dismayed. San Diego County and DWR received multiple public comment letters protesting the stipulated agreement and adjudication process.

In response to this backlash, the parties to the negotiations hastily convened public meetings to discuss the stipulated agreement. They eventually compromised on converting the draft GSP into a Groundwater Management Plan (GMP) to be submitted to the courts as an attachment to the stipulated agreement. Ultimately many Borregans came to accept the stipulated agreement, in part due to the perception that it may result in expedited water use reductions, faster than the GSP process would have.

The Stipulated Agreement/GMP was submitted to DWR by the January 31, 2020 SGMA deadline and is awaiting review. If accepted by DWR as compliant with SGMA, it will be assigned to a California Superior Court judge. If certified, the basin will be overseen by a district court judge and managed by a Watermaster Board composed of pumpers and community representatives. The court ruling on the Stipulated Agreement/GMP has since ground to a halt, as the world deals with the Covid-19 pandemic; progress will not be made until the state court system reopens.

Community Perseverance through the Water Master Board

Ever-proactive Borrego, though, is not deterred. An interim Watermaster (WM) Board is already convening and establishing its governance. Following the initial resistance, parties to the stipulated agreement are taking more care to include the community in this process by holding public meetings and including a community representative on the proposed WM Board. The board consists of 5 members, representing agriculture, recreation (golf and parks), BWD, community members, and the County. On June 3, 2020 the San Diego County Board of Supervisors voted in favor of having representation on the WM Board, and appointed County Water Resources Manager Jim Bennett, to its seat. The interim Watermaster Board is conducting business of the stipulated agreement for the time being, becoming permanent if DWR and the Superior Court judge rule in favor of the agreement. It could still be years before all the details of the Stipulated Agreement and Watermaster Board are worked out.

Still, many Borregans are relieved that there is at least a plan in place for their water future. The road to sustainability will be strict and difficult, requiring earnest commitment – but at least there is an agreed upon path to get there. With a required 75% reduction in water use over the next 20 years, the community must indeed embrace the changes to come. But if the desert wildflowers can blossom with such little water, so can the community of Borrego Springs. Borrego’s water challenges open the door of opportunity to envision the community’s future as a vibrant, thriving desert community.

LGC is helping the Borrego Valley Stewardship Council establish its role in determining that future. San Diego County will be updating Borrego’s Community Plan (as part of the County General Plan) in the next few years. Now is the time to unite the community in defining the vision for its own future. Through robust community engagement and integrated planning, BVSC hopes to align the efforts of the Watermaster Board/GMP with the Community Plan update, while also incorporating other local priorities – such as economic development, public health, and climate resilience. Exciting times are still ahead for this small desert town.