Amidst drought, groundwater regulation, and economic hardship, the media portrays Borrego Springs as a village “drying up” in the desert – running out of water – soon to be the next California ghost town. Like many aspects of the desert, there’s more to the Borrego Springs community than meets the eye. In the crevices of the valley’s rocky floor, wildflowers blossom in exuberant hope. In the shade of the Palo Verde trees, Coyote Creek babbles through the sandy slopes with perseverance. From corner to corner, the community is banding together: evaluating how to live within the constraints of this remote locale, charting a course that integrates civic engagement with environmental, social, and economic priorities – to achieve their goal of a thriving, resilient future. This is their story.

For over 50 years, Borrego Springs has celebrated the beginning of the tourist season with its annual “Borrego Days” festival, held at the end of October. This event is an emblem of tourism’s importance to the community, as well as its long history as a resort community. Lures to the Borrego Valley include golf courses, clean air, dark skies (Borrego is one of the few International Dark Sky Park and Communities in the world; you can still see the milky way here!), art, grapefruit, and friendly people (not necessarily in that order!). But the 900 square mile Anza-Borrego Desert State Park surrounding the town, with its stunning wide-open viewsheds, hiking, camping, and 4-wheel drive vehicle exploration, is the main attraction.

Park staff, volunteers, and local businesses band together each spring to support the rush of visitors from far and wide coming to witness the desert wildflower bloom. This is not only the time when the park receives the majority of its entrance fees but also what the entire town depends on to earn enough income to make it through the long summer months when business wanes. The park is the crown jewel of the region, but the Borrego Springs community is the heart of the park.

Some of Borrego Springs’ greatest charms also contribute to its most difficult challenges. As a remote, desert town surrounded by mountains and only accessible by long, winding two-lane roads or private planes, it’s difficult to get into and out of. This is also why it has very limited public services. The community does have a fire station and a medical clinic, but emergency services are a two-hour ambulance or quick helicopter ride away. There is no public transit, and local governance (the San Diego County Board of Supervisors) is 90 miles away.

Over the years, many have discovered the Borrego Valley and left their mark – some as full-time, year-round residents, others as seasonal visitors or weekenders. The town slowly grew. Change is subtle, but noticeable to the locals. The Borrego Springs population is highly seasonal, as much as doubling in the mild, winter months when part-time residents from colder climates flock to the desert. Borrego is a two-tier resort community: those who have the means to travel, spending their time and money in Borrego Springs; and those who support the service and tourism industries the others rely on.

Beneath the surface of Borrego Springs’ resort-style retirement community veneer, hardships exist. Over half of Borrego’s households (51%) earn less than $36,000 per year, and yet the average income in the community is $65,000 per year. A wide income disparity exists between weekenders who have second homes in Borrego Springs and those who live here year-round. The vast majority of Borrego Unified School District’s 400 students (92%) qualify for the Federal free and reduced lunch program. Borrego Springs is considered by the state of California to be a “Severely Disadvantaged Community” (SDAC) and an “Economically Distressed Area” (EDA).

Yet Borrego Springs does not feel disadvantaged or distressed; it is a friendly, generous, and caring community. People in Borrego Springs look out for one another. Neighbors help neighbors, and businesses help the community. The current COVID-19 crisis is a perfect example. With limited resources, the community has banded together in a heroic response effort to those who need food, rent, utilities, and gas. The town has no Family Resource Center so local families turn to Food Banks, the Borrego Ministers’ Association, and other independent groups for assistance. The town is amazingly supportive and philanthropic in its contributions to its people. They are a model for giving and support. In a single day, an independent group formed by two local Borrego Springs contractors, Fredericks and Wermers, distributed food to over 100 families. They will continue this weekly for as long as needed. Their food program is completely funded by private contributions.

The adage “it takes a village . . .” has true meaning in Borrego Springs.

A group of active Borregans have been working to preserve all that makes Borrego Springs special, while also ensuring a sustainable and resilient future for years to come. The Borrego Valley Stewardship Council established a charter in 2014 and is now making strides to integrate water management, land use planning, and economic development in the community. To envision the future of Borrego Springs, though, we must understand its past.

Long before the Borrego Valley was “discovered” by western explorers, native peoples known to us as Cahuilla inhabited the area. The Cahuilla, comprised of small kin-based bands, spent their winters in the Borrego region, then moving to the Laguna and Santa Rosa mountains in the spring through fall. The secret of life in the Borrego desert is the availability of water. Groundwater bubbled to the surface in a few oases, and the creek running through Coyote Canyon provides water year-round. Water enabled the Borrego region to serve as a crossroads for many historic episodes from earlier times.

Mexican explorer Juan Bautista de Anza found a route to the Presidio of San Francisco through Borrego’s Coyote Canyon, leading a caravan of over 200 migrants and 200 stock animals between 1774 and 1775. From the 1880s to the 1920s, the Borrego Valley was settled by non-native homesteaders with small farms and cattlemen wintering their herds in the desert.

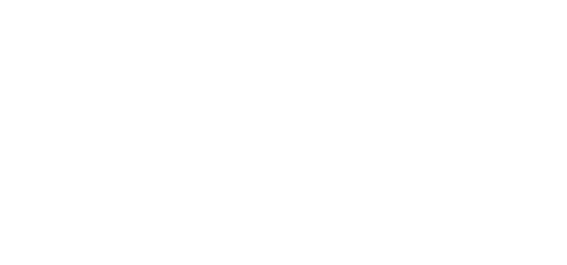

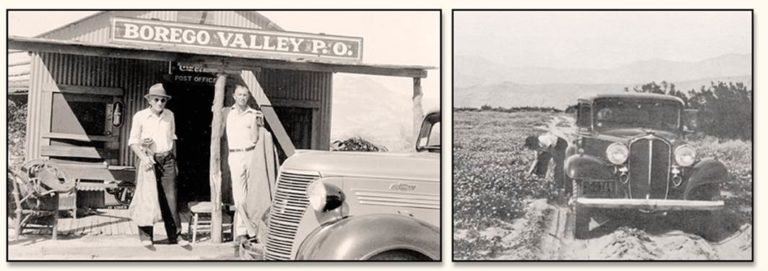

The roaring twenties brought automobiles and development to the Borrego Valley, including a small store, auto repair shop, a post office, and the first irrigation well. Easier access to water then enabled larger-scale agriculture. Little did they know at the time that Borrego’s aquifer, easily tapped a mere 40 feet under the valley floor and seemingly endless, was Borrego’s only source of water, and was actually quite limited.

The future looked bright for Borrego Springs at the close of the 1920s, as the population grew and The San Diego Union reported that: “This long-neglected land of long-recognized agricultural possibilities is on the eve of what is predicted will be one of the most interesting developments in San Diego’s backcountry.” Families in the valley, passionate about their chosen home, formed the “Borrego Springs Township.”

During this same era, California’s new State Parks Commission was surveying the state for “sufficiently distinctive and notable” locales to protect. At the prompting of famed landscape architect Frederick Olmstead, the Parks Commission had its eye on the ‘Borrego Desert’ with an ambitious million-acre desert park plan. They started, however, with a more modest Borrego Palms State Park in 1932. This designation, and claims that the park would rival Palm Springs, sparked further investment. The State Park, and Borrego’s comparison to Palm Springs, factors largely throughout the history of its development.

A.A. Burnand Jr., Joseph DiGiorgio, and James Copley are Borrego’s most notable developers and agriculturalists, responsible for much of the Borrego Springs we see today. DiGiorgio in particular was well aware of the value of water in the desert; resorts and golf courses cannot grow without it. DiGiorgio is responsible for getting electricity to the Valley (in 1945), enabling him to drill new groundwater wells, and pump that supply up to the surface. Now, large-scale agriculture was possible in the valley. DiGiorgio, Copley, and Burnand Jr. formed the Borrego Valley Golf and Improvement Company, and in 1949, built Country Club Road properties and the Desert Club. This swanky club for the nation’s rich and famous still stands but is now the world-class Steele/Burnand Desert Research Center, managed by the University of California, Irvine.

By the 1950s, Borrego Springs was both a quaint resort hide-out for the elite and an agricultural powerhouse. At its peak, over 3,000 acres of Borrego Valley were under cultivation, including cotton, flowers, date palms, citrus, and tree farms followed. Seeley Farm Red Grapefruit and Borrego Pink Grapefruit are still signature products today, sold exclusively in Borrego Springs. In 1957, Borrego State Park and Anza Desert State Park merged to become Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, closing in around the town. Borrego Springs as “the donut hole for development” in the middle of the park was born.

Borrego’s history carries forward through the present. DiGiorgio and Burnand designed the layout of Borrego Springs as we see it today, and built the first ‘downtown’ mall. The Old Borego Store and Post Office (original spelling) hosts an annual “old-timers” event, to celebrate the region’s rich history. Descendants from those original founding families still reside in the community. Mr. DiGiorgio recruited workers for his grape vineyards from the Guanajuato region of Mexico, and many of those families remain as long-term contributors to Borrego Springs. These families are the fabric that stitches the community together, uniting Borrego’s history with its future. Struggles over the region’s limitations, especially its limited groundwater supply, strain that community fabric.

Even as Borrego Springs was being advertised as a desert resort oasis in the 1960s, the locals were recognizing that water was the greatest limiting factor to their prosperity. A study conducted at that time suggested that the aquifer was already in overdraft. Some began guessing how much water was left in the aquifer, and how long it would last. Others ignored the issue. Then in 1982, the County of San Diego commissioned a study of the Borrego Valley aquifer by the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

The USGS hydrological report determined that the aquifer recharged with water at the rate of ~6,000 acre-feet per year (imagine 1-acre foot is the area of a football field, filled with 12 inches of water). The report also suggested there were roughly 3 million acre-feet of water in the aquifer. This data became a figurative football, as each interested group interpreted it to suit their own needs. Would the water in the aquifer last 50 years? 100 years? Did anyone really know, or even care? At one point, the State of California Department of Water Resources estimated there was nearly 500 years of water left in the ground! This debate continued into the 1990s, uncertainty allowing each generation to kick the proverbial can further down the road.

Farmers, responsible for about 70% of local groundwater use (not to mention a large portion of the local economy and jobs for community members), were defensive about their rights to the water; California water law sided with their view. With no one willing or able to control groundwater use, community leaders hoped a free market solution would emerge: someday, water would become harder to pump, and thus more expensive. The highest value water use would remain, and all others would dissipate. But this could also mean water may become too expensive for local residents, too.

California’s 1986-1992 drought got everyone’s attention. Water management – in Borrego Springs and across the state – was once again a top priority. The California Legislature responded with AB 3030; the Groundwater Management Act empowered local agencies to develop groundwater management plans. The Borrego Water District emerged as the responsible party for the Borrego groundwater basin. More than a decade later, Borrego Springs is still working toward a definitive answer and resilient solution to its water problem. Now, we hope, the community has the collaborative capacity and dedication to succeed.

When you drink the water, remember the spring. Chinese Proverb.